Baltimore City Paper, November 8-15, 2006

Q&A

By Lee Garder

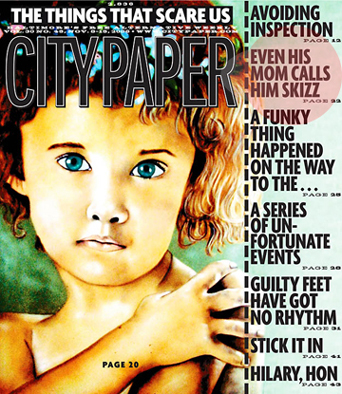

photo by Sam Holden

Not only is Paul "Skizz" Cyzyk undoubtedly one of the nicest men in Baltimore, but he's also one of the busiest and, when it comes to the local film scene, one of the most integral. In the early 1990s, while walloping the drums for punky pop trio Berserk and working on his own movies, Cyzyk also launched a we-run-what-you-brung film series in the living room of the former Waverly funeral home where he lived. The Mansion Theatre, as the house became known, provided a crucial forum for local underground filmmakers and attracted envious filmmakers from far beyond the 410 area code. When out-of-towners started buttonholing him in earnest in 1997, he started MicroCineFest, which has gone on to become one of the most prominent and idiosyncratic underground film festivals in the country. As Cyzyk, 40, prepares for the 10th annual MCF, he still somehow finds time to play music (in Garage Sale and the Jennifers, among other configurations), license a bunch of his archival material for the new documentary American Hardcore, work on his own movies, keep up with his day job as programming manager of the Maryland Film Festival, and sit down to talk to City Paper.

City Paper: Do you remember the first movie you ever saw?

Skizz Cyzyk: It was a double feature, and it was a drive-in, though I don't remember which one. It was Herbie the Love Bug and Jungle Book. To this day I still love Jungle Book. The Love Bug I'm not sure I could sit through.

CP: Did films grab you early on?

SC: Not really. About the time I was about 10 or 11, I borrowed an 8-mm projector from my grandmother and discovered that you could sign out 8-mm films from the library. So a lot of my summers were spent in the basement watching Nosferatu and a six-minute version of Night of the Demon. But I didn't really think about filmmaking as an art until high school, when, I think within the same week, I saw A Clockwork Orange, Liquid Sky, and Pink Floyd's The Wall, and it suddenly hit me: Hey, films are more than just entertainment. They can be art, they can say something, they can make you feel things. From then on, I wanted to be a filmmaker.

CP: You also play music, obviously. Has it been tough to do both all these years?

SC: That's probably been my problem all along. If I could just pick one that I could devote more time to, I'd probably be a little more successful with that one thing. But I can't do one and not the other. I like to try to combine them, because that way I get to do both.

CP: Between your work with the Maryland Film Festival, MicroCineFest, and the Mansion Theatre before that, you've been involved with showing films in Baltimore since . . .

SC: Since 1984. (laughs)

CP: What made you want to show films in addition to making them?

SC: Well, I started college in 1984, which is also when I started setting up punk-rock shows around town. I had friends who were in film classes, and they made these fun little movies. They would show them in class at the end of the semester, and that was it. And I thought it was kind of a shame that more people couldn't see these films. So I started including films between bands at the shows I was setting up. I did that for a little while, and then I really didn't do it so much until I moved into the Mansion. By that time I had graduated from college and had a film of my own and nowhere to show it. I realized there were a lot of other people in the same boat, so I decided to open up an outlet for people like that. It was an open screening, so any filmmaker who wanted to show up with something, I'd put it up on the screen--which wasn't always a good thing. (laughs) Of course, that blossomed into not just local films but films from all over the world, and that blossomed into MicroCineFest, and MicroCineFest got me the job at Maryland [Film Festival]. It's just been a big snowball. A career in film festivals that I never planned on, or even wanted.

CP: I remember seeing Chris Marker's La Jetée for the first time at the Mansion.

SC: That was actually a 16-mm print from the Pratt. They had this amazing collection that I didn't feel anybody was utilizing enough, so I'd always have a stack of their films ready in case nobody brought anything to show.

CP: You still remember the specific screenings you had?

SC: I tried to keep track of everything that was shown, and I put that on our web site. I just always sort of had this feeling like if you document things while they're small and not quite as important, if they grow into something bigger, people will want that documentation. You never know if something's going to grow into something bigger. This documentary that I've been making is about a bunch of guys who did some really cool stuff in the '70s, and they documented a lot of it, but they didn't document enough of it so that a filmmaker like me has what he needs.

CP: It's like Dogtown and Z-Boys. That film pushes the point that skateboarding was this radical thing and nobody was paying attention, and yet they seem to have done almost everything they did in front of a camera.

SC: Which ties into American Hardcore. I just took all these photos at hardcore shows in Baltimore and D.C. between '83 and '86. I never knew what I would do with them. They sat in a shoebox for years, and then along came a friend making a documentary about hardcore. Next thing you know, he's using two dozen of 'em in this film that Sony has in theaters across the country.

CP: Are there any films or filmmakers from the Mansion screenings who have gone on to wider renown?

SC: The one thing that comes to mind is that we showed a short by Brian Dannelly, who went on to make Saved! When he came to town for the Maryland Film Festival, he came up to say hi to me and told me he remembered that screening and how much it meant to him. That's an example of somebody feeling confident that his early work was good. It was kind of touching. This little hobby made a difference for somebody.

CP: When you started MicroCineFest during the final years of the Mansion, did you ever think it'd last a decade?

SC: No. I had no idea how long it would last. We were actually ready to stop it after the third year. In fact, we had decided that's it, we're not doing this anymore. And then I saw a film that I loved at a festival and thought, We need to show this. And then we decided that's going to happen every year, so we should just keep doing it. This year, we're trying not to let the fact that it's the last year overshadow the fact that it's the 10th year. I'd rather be celebrating the 10th anniversary than the final year.

CP: So this is officially the last one?

SC: MicroCineFest the organization will still exist, but the annual festival won't. I'd still like to do some screenings when something good comes around, but I've got a documentary that I've been working on since 1999 that I never have time to work on. I want to stop spending my summers watching entries and stop spending my falls making phone calls and e-mails and running all over town. We'd like to work on our house. (laughs) We just felt it was time. People always say, "You say you're not doing it anymore every year." And I say, "Well, no, I always say that I might not do it anymore. This year I'm saying I won't be doing it anymore." (laughs) It's time for me to be getting back to what I wanted to do, which is make films and music.

CP: Tell me about the film you're working on.

SC: There's two, but the main one is, do you know who the Rev. Fred Lane is?

CP: And the Hittite Hot Shots?

SC: Right. He was part of a '70s arts community in Tuscaloosa, Ala., called Raudelunas, and they put out a bunch of records. Two of the Fred Lane records are two of my all-time favorite albums, and I just always wanted to know more about them. Then in 1999 I was researching a documentary I wanted to make about outsider music, and during that research I found a web site fan page by a guy in Scotland who had actually tracked down Fred Lane. And through this guy in Scotland, I got in touch with everybody involved in this whole Raudelunas scene, and since 1999 I've been traveling all over the country shooting interviews and hoping to one day edit it.

CP: What's the other one?

SC: Do you know the movie Urgh! A Music War? I was trying to make a documentary about that that would be on the festival circuit for the film's 25th anniversary--which I missed. But everybody I talked to that knows of that film from back when it came out, in 1981, it was a very important part of their musical upbringing, but to this day, it's very obscure. It turned me on to so many bands that to this day are still some of my favorite bands. I've always told people it would be the Woodstock of my generation if my generation had cared about cool music. So I just can't believe that 25 years later that it's still so obscure, especially with so many popular bands basically ripping off the bands that were in there. (laughs) So far all I've done is whenever anyone involved with the film has come to this area, I've interviewed them--the ones that would let me. The Cramps turned me down. Stan Ridgway from Wall of Voodoo ignored me, Andy Summers [of the Police] ignored me. But I've got interviews with Stewart Copeland, John Doe, David Thomas from Pere Ubu, Steel Pulse, the Fleshtones, Gary Numan. It was a real thrill to interview Gary Numan. (laughs) I made him laugh! I've never even seen a picture of him smiling. I got to spend an entire evening with Devo--they're one of my favorite bands since junior high. It's been fun to work on, but I don't know when I'll ever finish it.

CP: You've got a big program of New Jersey filmmaker Matthew Silver shorts in this year's festival. He sort of seems like a poster child for the sort of filmmaker MicroCineFest has championed, and who it probably matters to most.

SC: I'm really proud of that program. He said to me that he was a little concerned that he's a nobody and we're showing 90 minutes of his stuff, and I tried to tell him, "You are not a nobody at MicroCineFest. You have fans in Baltimore." The right people are going to love that program. Everyone else might walk out, but . . . (laughs) He makes very low-budget productions that are so offbeat that they're not likely to find audiences at regular film festivals. He's not even sure how he feels about his work, because he doesn't quite get the acceptance he was expecting, but at MicroCineFest . . . his stuff just belongs here. I'm hoping that since we're going to stop doing festivals and we're having this big program, that the other MicroCineFest-esque festivals around the country will contact him.

CP: DVD and things like YouTube have changed the game for more mainstream films. In the past 10 years, have you seen things change for underground films?

SC: It's gotten good for the films and filmmakers, but it's gotten bad for MicroCineFest. We were always an outlet for these outcast filmmakers that couldn't get their stuff seen anywhere else and were desperate for an audience. These days any filmmaker in that boat has YouTube, and YouTube's going to help them reach a much bigger audience than we ever will. It's already happened that I've seen something on YouTube that I would love to show at MicroCineFest, and the filmmakers don't want to be bothered. They're getting their exposure, so why send me a tape? It kind of breaks my heart, because there are some films that I just know that our audience would love, and I don't want to just, like, send everybody a link.

CP: Does the world of underground cinema start to get to you so that you have to, like, go out and see a Sandra Bullock movie or something?

SC: I've never been one of those anti-Hollywood snobs. Hollywood's job is to make entertainment to people, and they do it well. When I want to go see an entertaining movie in a theater, it's there for me. There are plenty of underground films that entertain me, too. I don't even consciously divide them into indie or underground and Hollywood. When I'm watching the [Microcinefest] entries, I will get so tired that I'll turn off the VCR and watch CSI. A couple of years ago we bought a really nice TV set--HD television looks really pretty. (laughs) I don't even pay attention to the stories--I just like looking at it.